Kant via Eichmann

When the Nazi official Adolf Eichmann, on trial in Jerusalem, was asked how he could morally reconcile himself to what he was doing, he gave an answer that would become notorious via Hannah Arendt’s chronicle of the trial: “all my life I have tried to live by Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative”. Asked to elaborate, he provided a tolerable paraphrase of Kant’s famous notion: “I meant by this that the principle of my volition and the principle of my life must be such that it could at any time be raised to be the principle of general legislation”. He began to flounder when the judge asked him whether he felt that forcibly deporting Jews corresponded to the categorical imperative.

There are many interesting questions to be asked about what, in light of Eichmann’s apparent allegiance, we should think about Kant’s moral philosophy. An advanced course on Kant’s moral philosophy might engage with questions like that.

What I don’t think anyone would argue is that the best way to introduce Kant’s moral philosophy is by way of Eichmann’s confused encounter with it. You wouldn’t want Eichmann teaching you Kant, so you wouldn’t want anyone teaching you Kant via Eichmann.

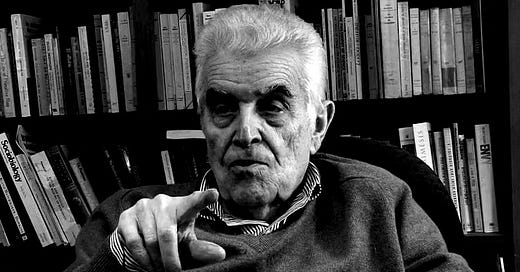

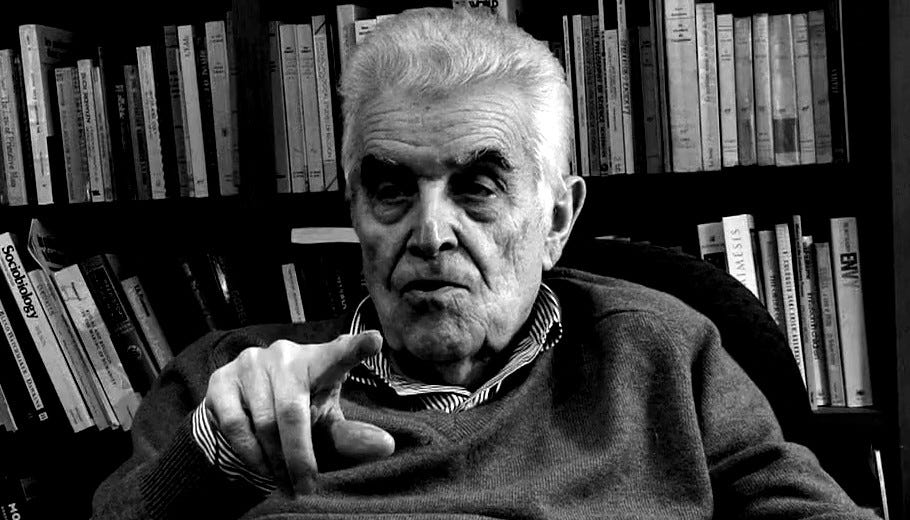

Girard via Vance

That, however, doesn’t seem far off the way that René Girard’s theories have been introduced to countless American audiences. I’m writing this post because I keep encountering newspaper articles and comment pieces presenting Girard in connection with right-wing figures in the USA. I was hoping to avoid commenting on the subject. I don’t think there is much of interest to be said about the pseudo-philosophy sloshing around political chat groups, and the American chattering classes have more than enough interest in themselves for all the rest of us. But it keeps coming up, so I feel compelled to write something.

It’s depressing but predictable that the thing the media should find most interesting about Girard is his connection to much less intellectually interesting figures: the tech entrepreneur Peter Thiel and the Republican vice presidential candidate J.D. Vance. It’s not that I think these men are stupid—events would suggest that they are superbly good at business and politics. But they certainly aren’t experts on Girard, and I don’t see why seeking to learn about Girard by looking at what they say about him makes any more sense than seeking to learn about Kant from Eichmann.

Worse, the fact that this has been the channel by which Girard has come to the attention of the American public means that the messengers have been highly imperfect. The pundit, blogger, or journalist informing the public of Girard’s influence on Thiel and Vance then goes on to “explain” Girard’s theories to the audience. The problem is that the pundit, blogger, or journalist is an expert on White House and Silicon Valley gossip, not on Girard.

A while ago I wrote a post correcting what I found to be an unfair and inaccurate treatment of Girard by the philosopher Justin Smith-Ruiu. I don’t blame Smith-Ruiu for getting these points wrong, given that his research covers a vast range of topics and he isn’t a Girard specialist. Occasional inaccuracy is the price paid for breadth and often worth paying. But if an academic philosopher can get Girard so wrong, imagine the level of accuracy you can expect from people who at most have time to sometimes skim a couple of paragraphs of Girard, in between trawling the blogosphere and fighting ten online flame wars at the same time.

I beg you not to learn about Girard from them. If you have time to read the 12,000 word blog post series on Girard by the political blogger John Ganz, then you have time to instead read at least one of Girard’s own essays, perhaps in the recently published Penguin collection (for the same reason, I won’t try to summarise Girard’s thought here). That is, if you want to learn what Girard actually thought—not if you want hot takes to spout on your podcast. My fear is that too many Americans now learning about Girard go into the latter category.

How Girardian Are They?

The other unfortunate consequence of the Girard-Thiel/Vance association is that it has started a competitive game of wild speculation on how the actions and pronouncements of these powerful men are secretly “Girardian”.

Start with Vance. The only reference to Girard I can find from him is in a 2020 essay describing his conversion experience. He reports that Girard’s theory of scapegoating, introduced to him by Thiel, was part of what moved him towards the Catholic Church. He learnt from Girard that:

In Christ, we see our efforts to shift blame and our own inadequacies onto a victim for what they are: a moral failing, projected violently upon someone else. Christ is the scapegoat who reveals our imperfections, and forces us to look at our own flaws rather than blame our society’s chosen victims.

This inspired him to reconsider his life choices:

Mired in the swamp of social media, we identified a scapegoat and digitally pounced. We were keyboard warriors, unloading on people via Facebook and Twitter, blind to our own problems. We fought over jobs we didn’t actually want while pretending we didn’t fight for them at all. And the end result for me, at least, was that I had lost the language of virtue. I felt more shame over failing in a law school exam than I did about losing my temper with my girlfriend.

That all had to change. It was time to stop scapegoating and focus on what I could do to improve things.

This wasn’t borne out in practice—not visibly at least. But even in principle it’s not very Girardian. Girard, as I read him, would find the very impulse to “improve things”—at least in the big, public, glorious way Vance appears to have intended—to be a patent expression of the mimetic, competitive, prideful drives against which his work was a warning. An article on Vance’s Girardism in the Catholic Herald ends a (comparatively quite good) summary of Girard’s thought with the statement: “we live in apocalyptic times, and the only viable option now is to withdraw from the world and develop our capacity for love”. It then goes on to discuss how Vance is applying Girard’s principles in politics, failing to note that doing so is precisely not taking the “only viable option” of withdrawing from the world. Nor does Vance’s campaigning seem to glow with the embers of love.

Indeed, Vance shows no sign of having stopped scapegoating. An article in Politico by Ian Ward makes this point, observing that Vance was happy to scapegoat Haitian immigrants for social problems—you can add them to the list of other scapegoats Vance has raised: single women, universities, the woke left, etc. Ward then draws a bizarre conclusion: Vance has consciously reversed course on scapegoating since his 2019 conversion, and he has done so for Girardian reasons. Having realised that Girard’s version of Christianity “cannot in practice serve as the basis for a large, complex and modern society”, Vance decided instead to make a how-to guide out of Girard’s characterisation of archaic societies as held together by common animosity towards a scapegoat.

To be sure, the accusations Vance makes against these groups—eating pets, for instance, or overriding their natural maternal instincts—line up quite well with Girard’s picture of the sorts of crimes scapegoats are accused of in archaic societies, which, as he says in The Scapegoat, “transgress the taboos that are considered the strictest in the society in question” (15). But it’s quite a reach, I think, to imagine that Vance has been inspired by Girard to reinstate archaic scapegoating rituals. A more plausible explanation is that Vance is a political opportunist. It doesn’t take a sophisticated theory of ancient rituals to see that there are always votes to be gained from bashing immigrants. If Ward knew Girard better he would know that a crucial part of the theory is that scapegoating no longer works to produce social cohesion, now that we are able to recognise the phenomenon thanks to the Christian revelation. Attempts to build social cohesion on scapegoating produce a mountain of victims but fail to achieve unity: there will always be a faction defending the victims and condemning the scapegoating. The Girardian Paul Dumouchel wrote a whole book on this. Anyone trying to use scapegoating for its original purpose is, by definition not a Girardian; they reject Girard’s whole theory of Christ’s place in history.

As for Thiel, the one “Girardian” idea he seems to have had is that competition is bad for business. In his book Zero to One, he presents this in a vaguely Girardian way, though he doesn’t mention Girard. He does use references to Shakespeare that he most likely picked up from Girard in classes and conversations at Stanford. But it’s not really a very Girardian idea. Thiel references a sort of mimetic trap, in which rival competitors cannot help but imitate each other, thus failing to innovate. Girard’s own thoughts on the relation between mimesis and innovation are much more sophisticated; a decent summary can be found in his essay “Innovation and Repetition”. The idea going around the internet, that Thiel “applied Girard’s theory to business” is about as true as the airport bookshelf cliche that a boss who plans ahead or seeks to befriend her enemies is “applying Sun Tzu’s Art of War to business practice”.

As with Vance, people have tried to look beyond Thiel’s explicit statements to find secret Girardian motivations behind his actions. Sam Kriss proposes that Thiel’s “business decision that most clearly bears Girard’s fingerprints is the $500,000 punt that turned Facebook into a behemoth”. But again, you don’t need Girard’s theories to see that Facebook might be a worthwhile investment. Kriss reports that “Girard has been described as the ‘godfather of the Like button’”—but there wasn’t even a Like button when Thiel invested in 2004. Again, giving Thiel’s business behaviour a Girardian interpretation seems like a reach at best.

Girard’s “Politics”

The most embarrassing feature of our age is its obsession with politics. The early moderns turned everything into a question of religion—hairstyles, architecture, rhyme schemes in poetry. This all got a bit silly (Nell Gwyn had to assure a crowd that she was the Protestant whore), but at least religion at its best expresses the noblest side of the human spirit. Politics is never anything but base. Turning any issue into a political campaign is, nine times out of ten, a way of saying: “and now to make it about my (or our) ego(s)”.

Much of Girard’s theory is primarily concerned with egotism, status-hunger, glory-seeking, and their mimetic causes and effects. In archaic societies these compounded, via mimesis, into unanimous condemnation of scapegoats. In modern society, the result is not unanimity but warring crowds. By definition this cannot be a political theory. When asked about his politics, Girard replied by effectively stressing his anti-political stance:

I would say that I'm a centrist, meaning I'm anti-crowd, the “mobilized crowd” Sartre dreamed of, and ultimately the scapegoat theory is fundamentally an anti-crowd theory. After all, the crowd tends to be completely on the “right” or on the “left” . An intellectual has the obligation to avoid such dichotomies.

He clearly didn’t mean that he believes in the ideals of the political centre. Political ideals are beside the point for him; what matters is where and how crowds form. The fact that there might be a crowd forming on the political right around a reading of Girard—according to Kriss, “Girardianism has become a secret doctrine of a strange new frontier in reactionary thought”—cannot be understood as a political application of Girard’s theories. It is precisely what Girard’s anti-politics condemns.

Girard had his allegiances, of course. He was a conservative Catholic who endorsed Benedict XVI’s Regensburg Address and occasionally criticised what he called “political correctness” as a hamfisted attempt to restore the system of crowd-policed prohibitions of archaic society. This might be part of what draws figures like Vance towards him. One of Vance’s few consistencies is his sustained hostility to “wokeness”, which to some extent plays the same role in 2020s conservative thinking as “political correctness” played in 1990s conservative thinking.

But notice the difference in terminology. “Political correctness” conveys a sense of superior priggishness for which the associated attitude used to be condemned. “Woke” is a term hijacked from African American Vernacular English. The word itself carries the signs of scapegoating: it tells you nothing about the attitude or ideology it’s meant to target, but it does tell you something about who is being targeted. It is straightforwardly an attempt to trigger the scapegoat mechanism, and, like all such attempts in the post-Christian world, it fails because some people defend and identify with the victims: in fact, many victimise others in order to do so. Anti-woke campaigning is Girardian only insofar as it cries out for a Girardian analysis; no less than “political correctness” it is a hopeless attempt to restore the patterns of archaic society—to unify the majority against a minority of victims blamed for social conflict.

Vance and Thiel are not Girardian in the sense of understanding, applying, or developing his theories. They are Girardian in the sense that their behaviour is explained by Girard’s theory. They are driven by a self-image they long to project in the world—the Entrepreneur, the Visionary, the Maverick, the Redeemer—that draws them along as a model for emulation. But that is true of anyone who pursues power, status, reputation, and influence—trying to conjure being out of our essential nothingness.

Doing this inevitably creates envy and rivalry with others. Anyone attempting to build a political coalition by channeling those feelings into hostility towards a scapegoat has either not understood Girard or thoroughly rejects his entire philosophy.

Thank you very much for overcoming your resistance and providing this simple and straightforward rebuttal of the notion that the words, writings and actions of Thiel/Vance accurately represent René Girard's theory or, worse, how he might have wanted to see it put into practice.

Couldn’t agree more! I find this distortion of Girard’s thoughts pretty appalling. Makes me think of Nietzsche’s own misrepresentation by the Nazis. And yes, better read Girard himself than any of his (politically biased) commentators. I’d even add: read it in French if you can, his prose is incredibly elegant and compelling, comparable to Bergson’s, for instance.